Dancing for our lives

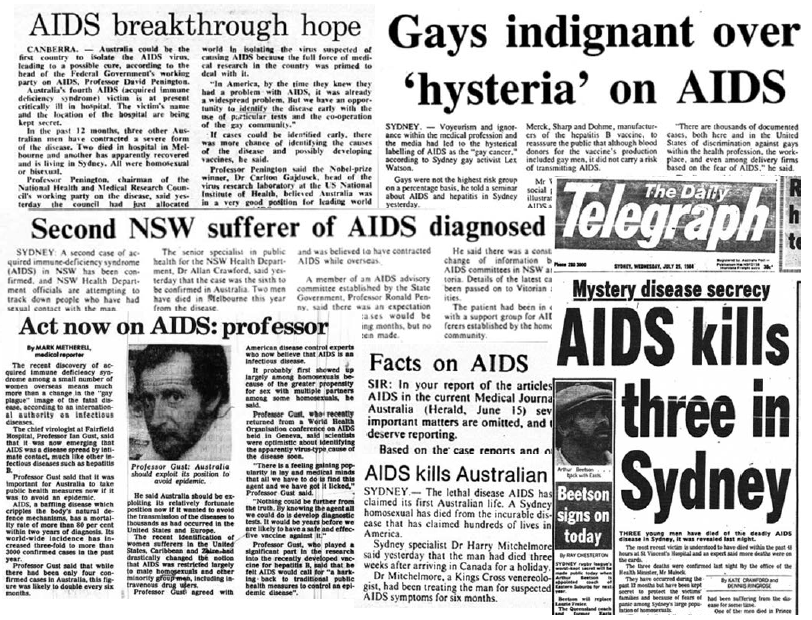

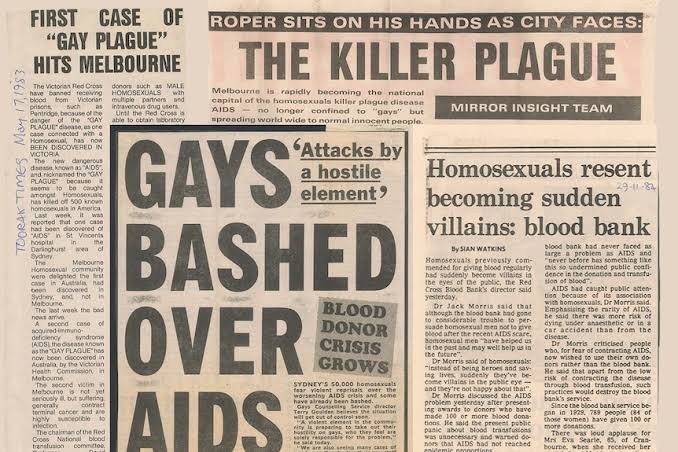

t a time when Oxford St and queer Sydney were beginning to find a united voice after the success of the annual Mardi Gras parade and parties, AIDS arrived. The disease reared its ugly head at the beginning of the 80s and the impact it would leave on the gay community would be felt for decades. The first newspaper article published on AIDS (Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome) was a piece written by Lawrence K. Altman entitled ‘Rare cancer seen in 41 homosexuals’. It ran in the New York Times in July 1981 and reported that gay men were dying from an unusual disease. First it was believed to be a cancer as symptoms matched a type seen only in old men but the men showing up were all young and relatively healthy. It was then discovered that the HIV virus was the cause of this cancer and survival rates seemed to be non-existent.

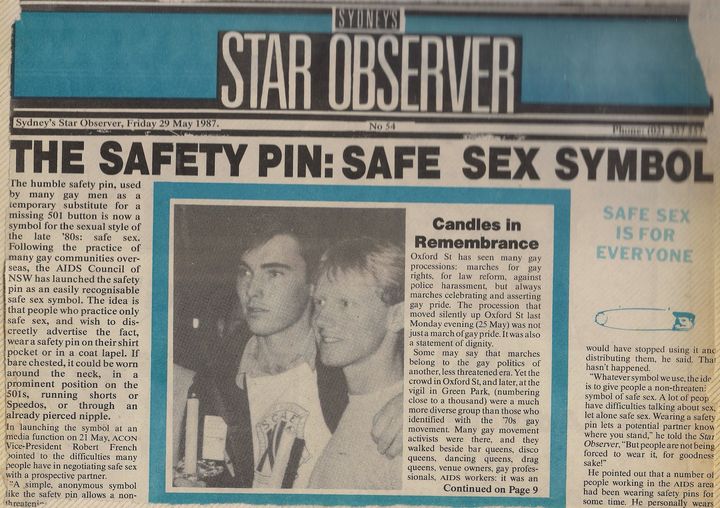

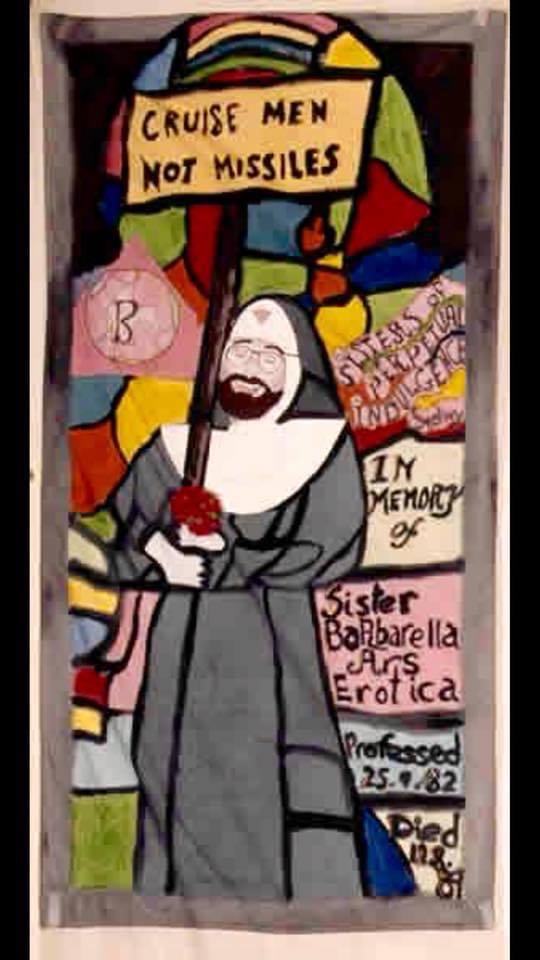

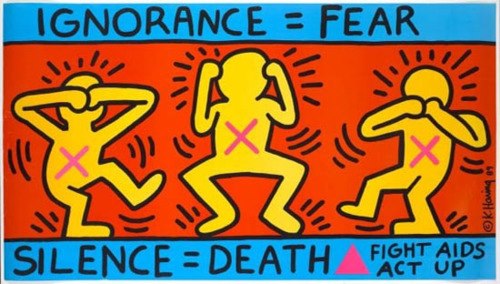

ay men were the prime target of the disease as sexual transmission seemed to be the main cause and although they had made great strides for Gay & Lesbian visibility, the disease became a lightning rod for the same old hate, anger and prejudice they had endured for decades. The press branded AIDS as the ‘gay plague’.

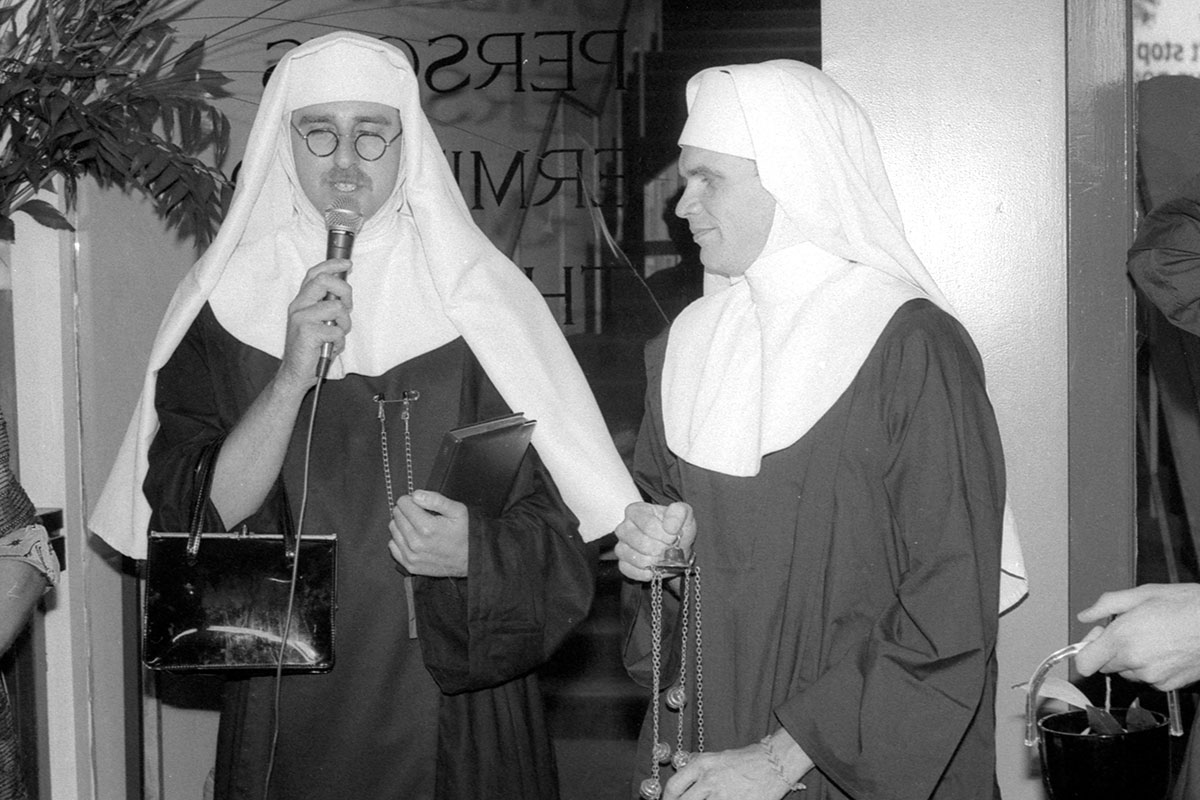

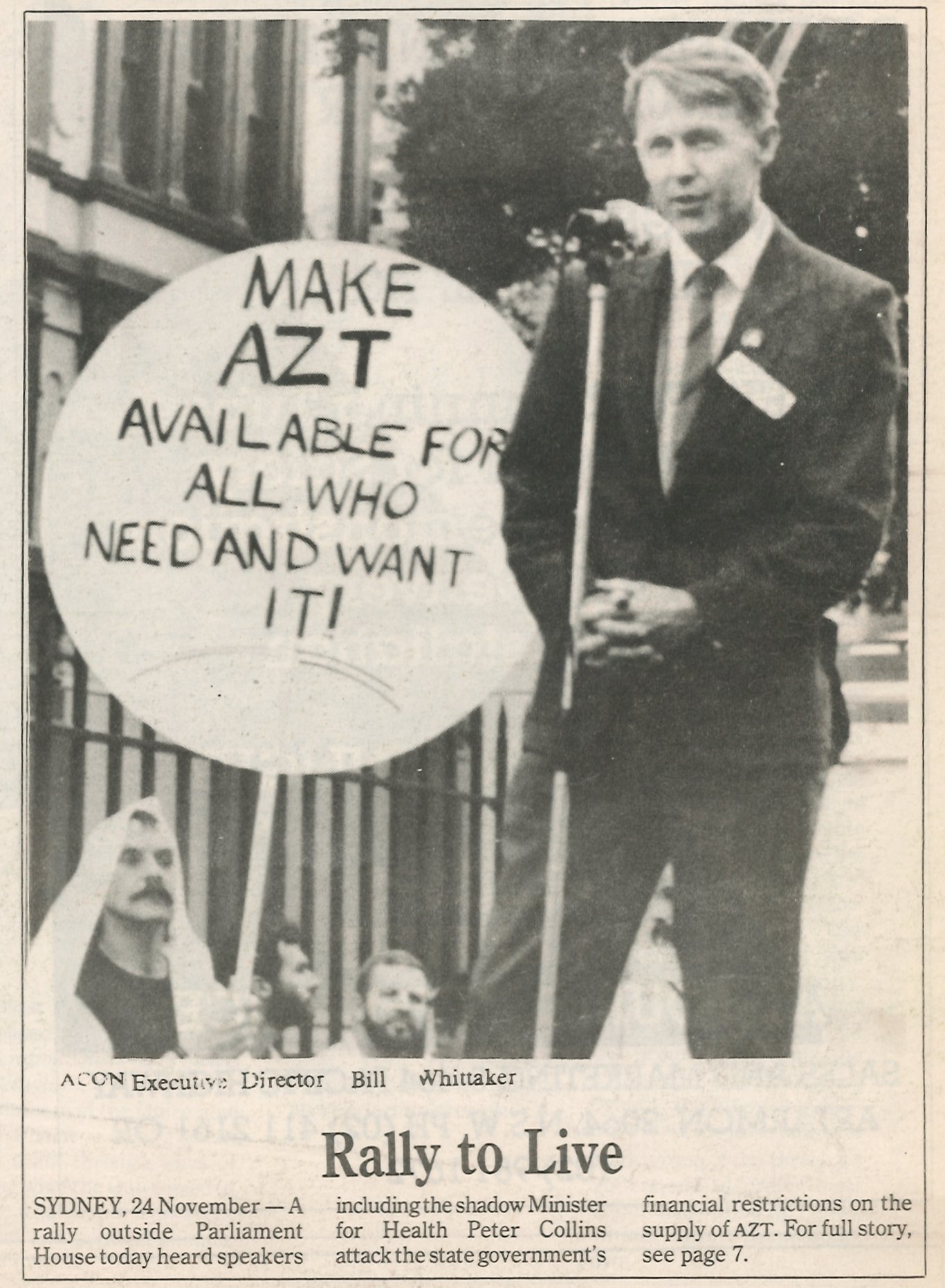

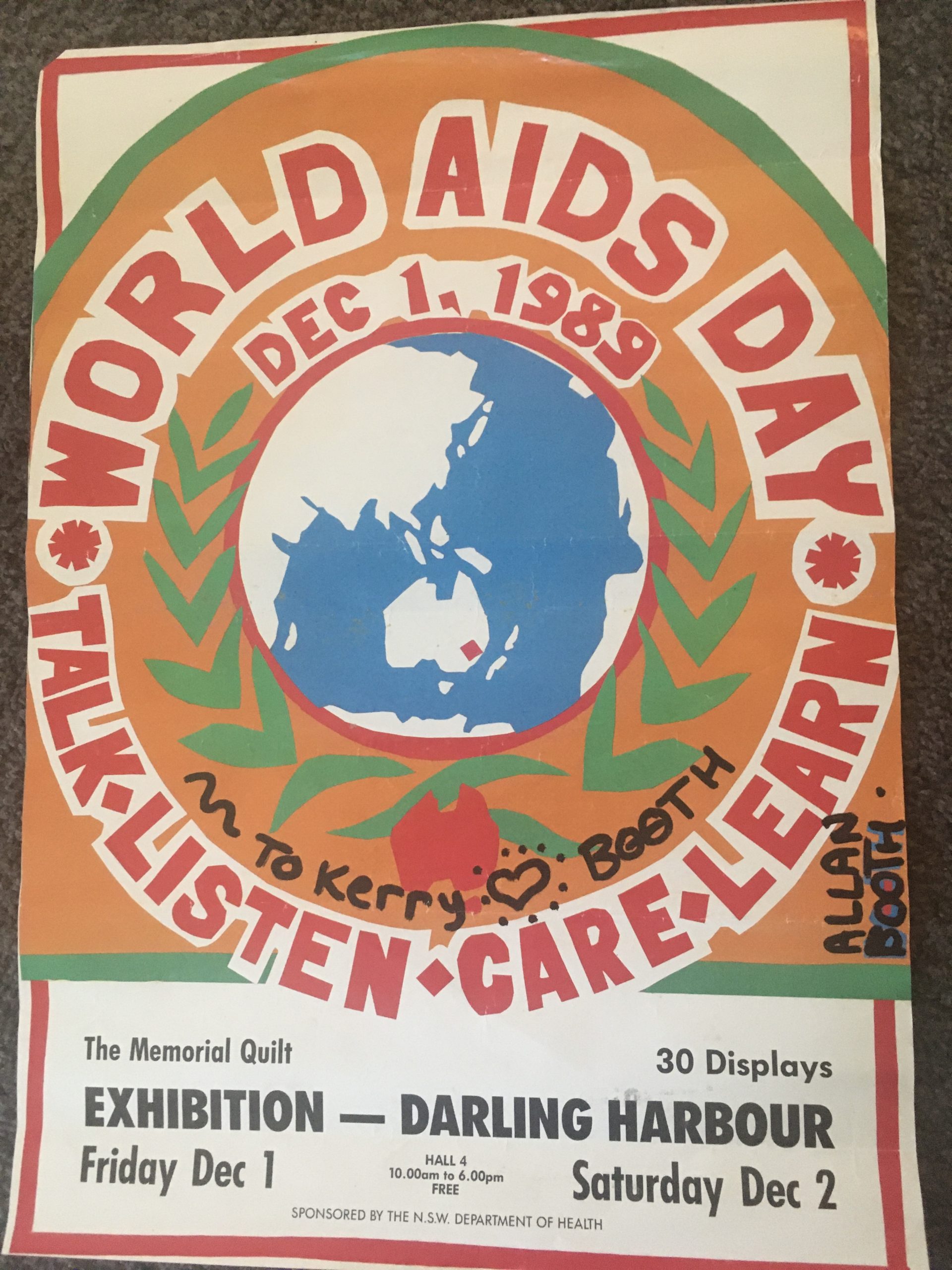

Australia, and especially Sydney, dealt with it better. Community groups mobilised early after seeing the inaction and neglect set by the Reagan administration in the States and the deaths that followed. We also had a new Labour government that was more sympathetic and aware of just how deadly the disease could become.

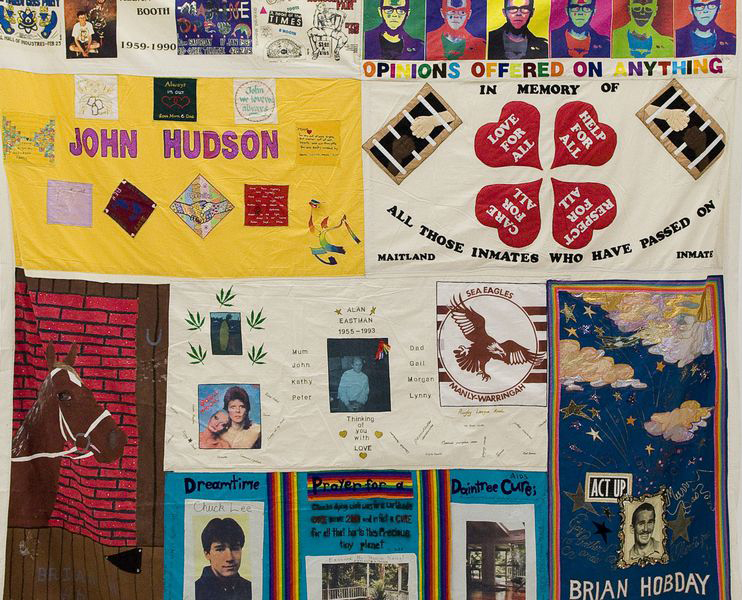

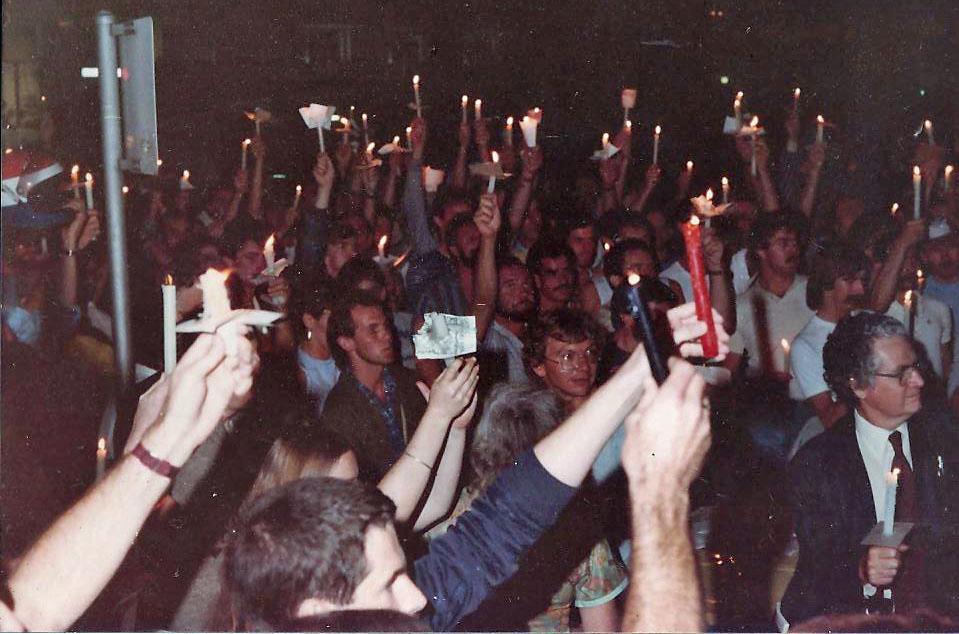

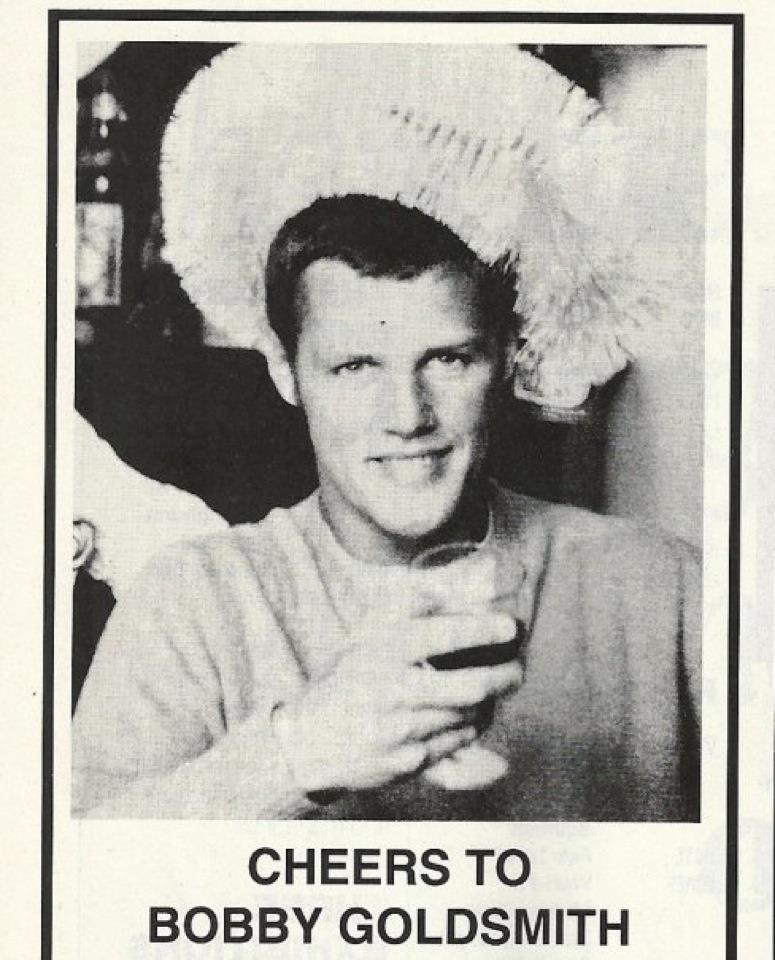

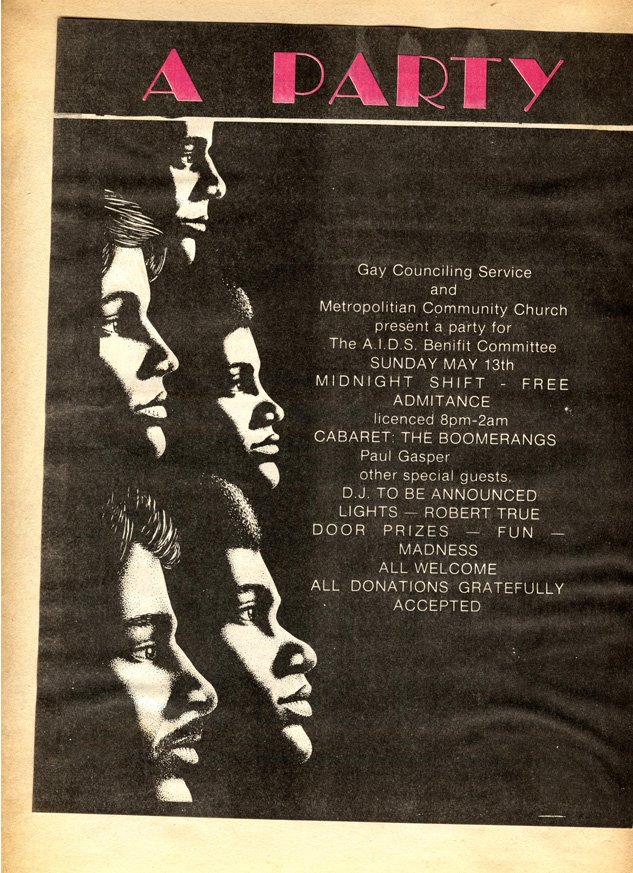

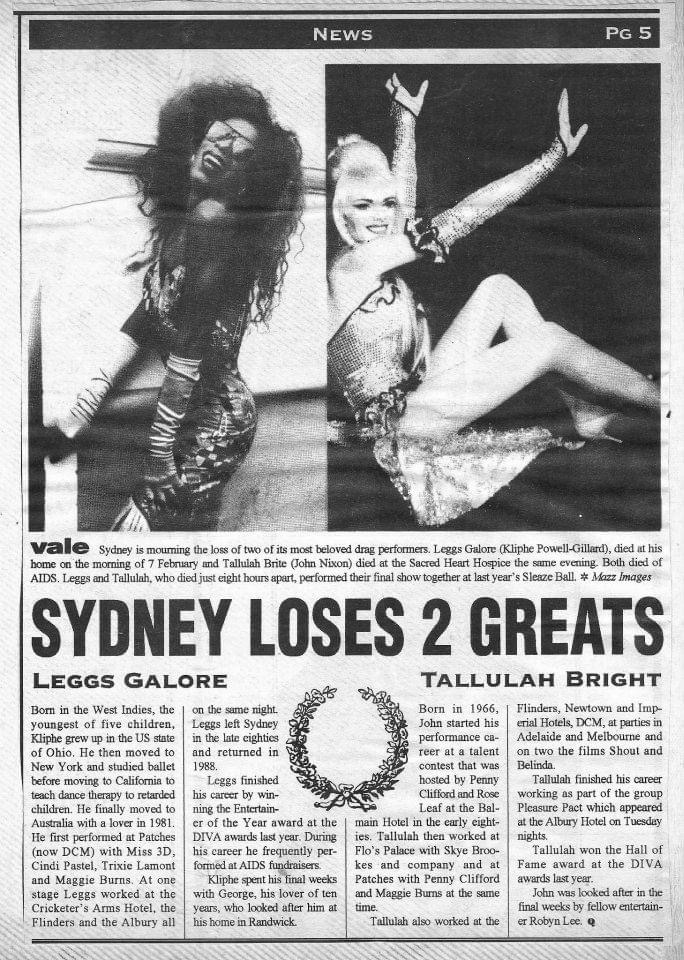

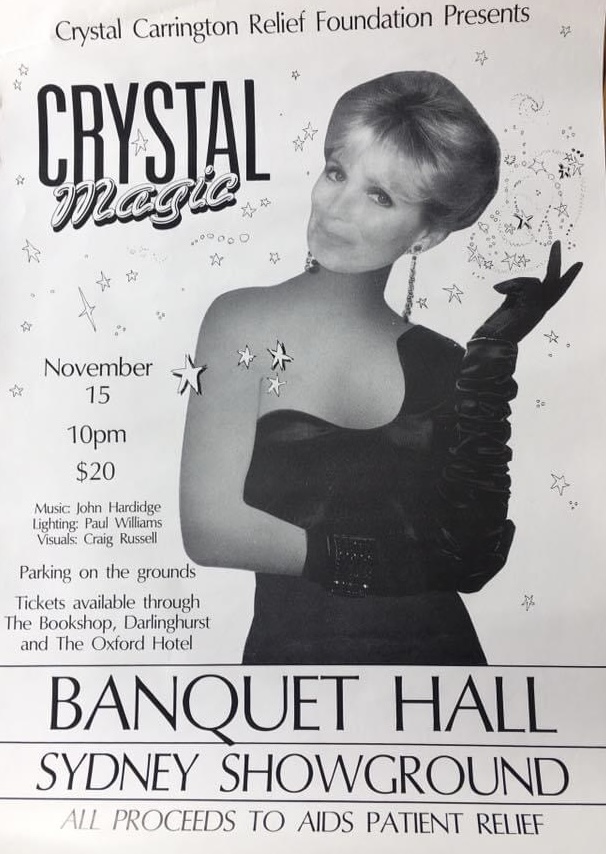

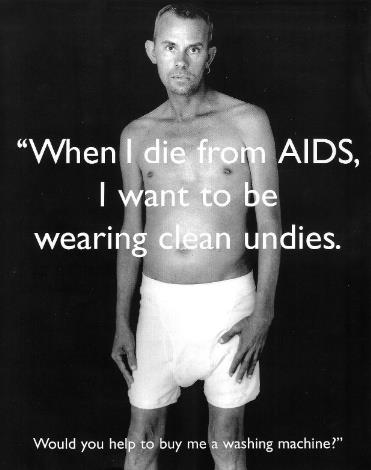

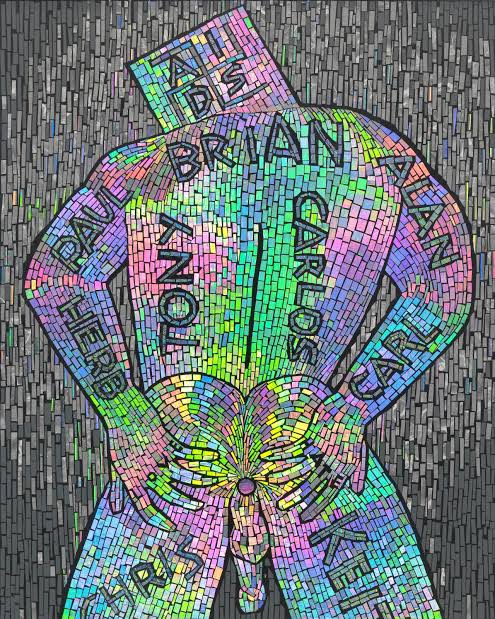

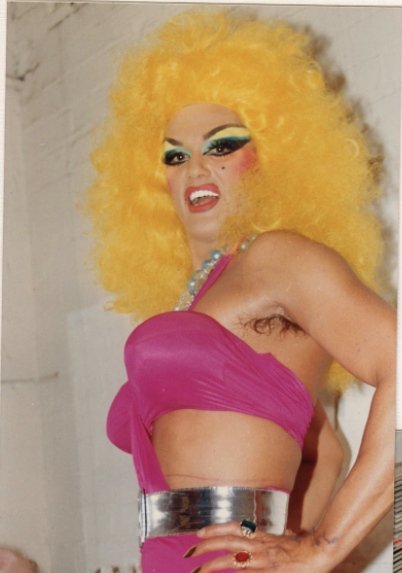

ur first AIDS death occurred in 1981, although his records weren’t discovered till years later. Bobby Goldsmith, a Gay Games medallist, was one of the first diagnosed in Sydney and after his death, the Bobby Goldsmith Foundation was formed, one of the first groups to begin helping people living with HIV. By the late 80’s, the disease had touched nearly everyone in Sydney’s queer community. Mardi Gras and the Hordern parties became a distraction to the devastation. Stories of ashes being strewn across the floor of the Hordern by loved-ones lost to the disease were common place. Other stories were told of dying men just trying to hold on so they could get to their final Mardi Gras, Sleaze or Hordern party. These parties were a lifeline, an escape, a last dance, a farewell to friends and families. Nightclubs had always been a sanctuary for gay men, a space where they could be whoever they wanted to be. The Hordern, or as everyone would call it Club Hordern, felt like home.

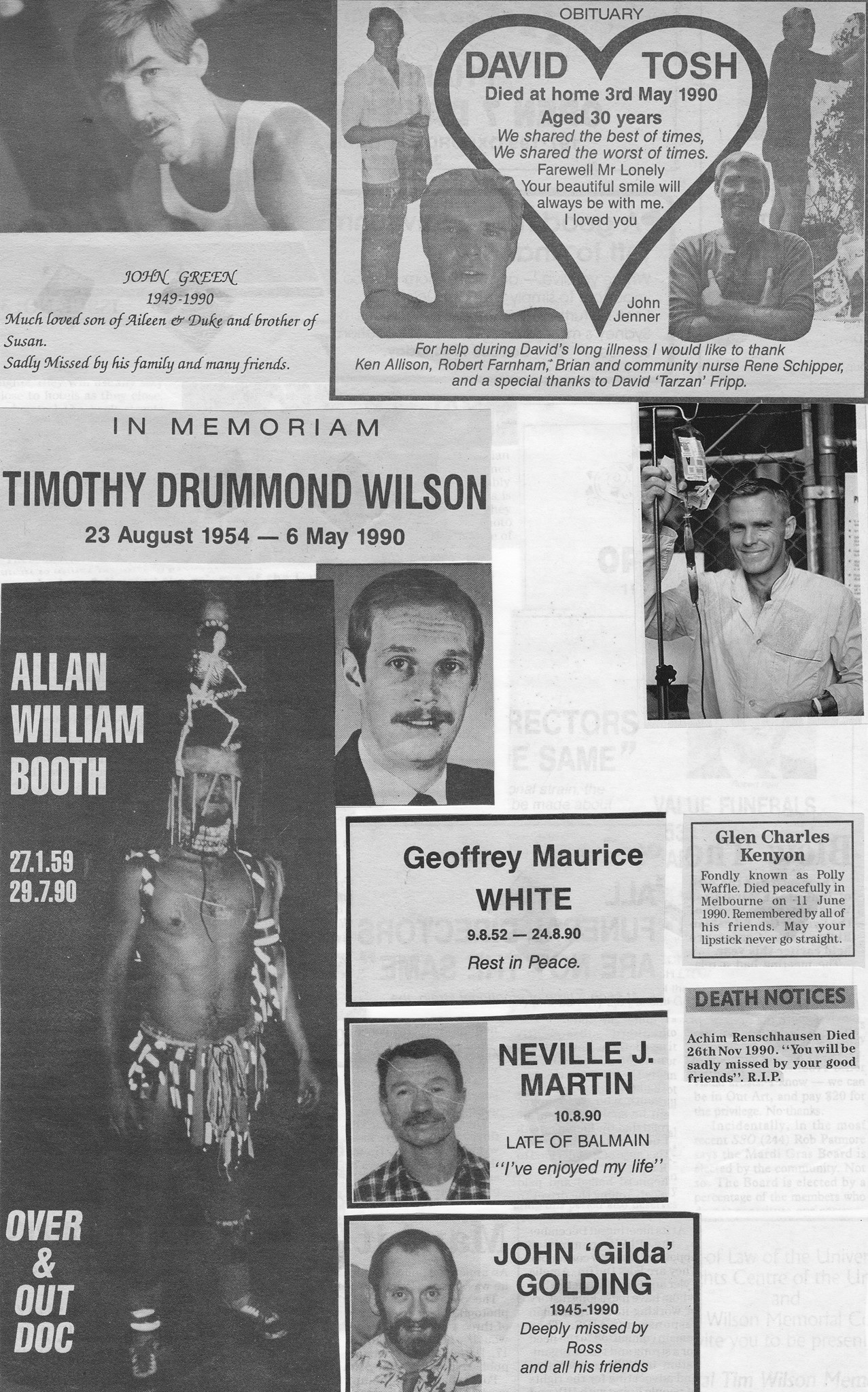

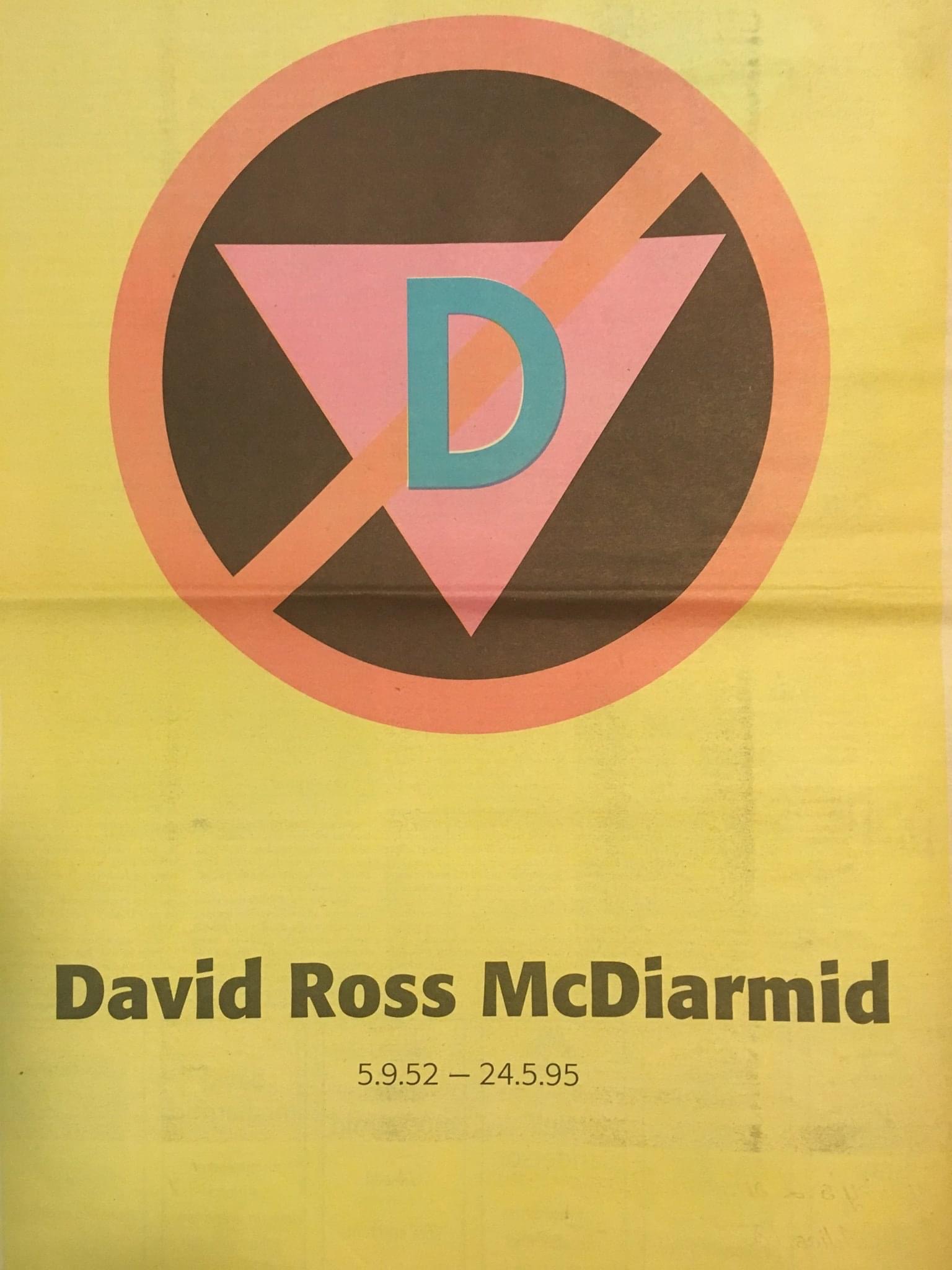

By 1996, more than 5000 people had died from AIDS in Australia, the majority in Sydney, and nearly 80% of them were gay men. The funeral notices in the gay press went from just a few ads in the back section to pages by the early 90s. It turned into an avalanche. But if AIDS did one thing, it was to bring the community closer together and to become more vocal in its right to exist. AIDS was as much about the Hordern story as the music, the dancing and the drugs and the community.